The Secret to Buying Low / Selling High

The secret to buying low

To make money investing, most experts agree you only need to do one thing: buy low and sell high. While this sounds simple, it’s one of the hardest things to do in practice. In fact, famous investors like Warren Buffett routinely mock anyone who says they’ve mastered this approach.

The challenge of timing the market? You may miss out on some of the best-performing days, many of which happen during downturns, bear markets, or otherwise volatile periods. These big surges can have a meaningful impact on your long-term returns, as can missing them.

Fortunately, there’s a way to approach buy low investing that doesn’t require you to time the market. It’s called dollar-cost averaging.

What is dollar cost averaging?

Dollar cost averaging refers to regular, consistent contributions to an investment account. For instance, if you set up automatic contributions to your retirement account from every paycheck, and those contributions get automatically invested, you’re dollar cost averaging.

Because these purchases happen on a set schedule regardless of market performance, you’re just as likely to buy low as you are to buy high. If the market falls, you end up automatically “buying the dip” without having to make a conscientious effort to do so. You also aren’t waiting for a dip to buy.

This consistency can help boost returns over time.

Consistency and performance

To understand how this strategy impacts performance, let’s go over an example. Keep in mind, this is meant to be educational—you can’t invest directly into the S&P 500 and individual results will vary based on your personal portfolio, contribution amounts, and more.

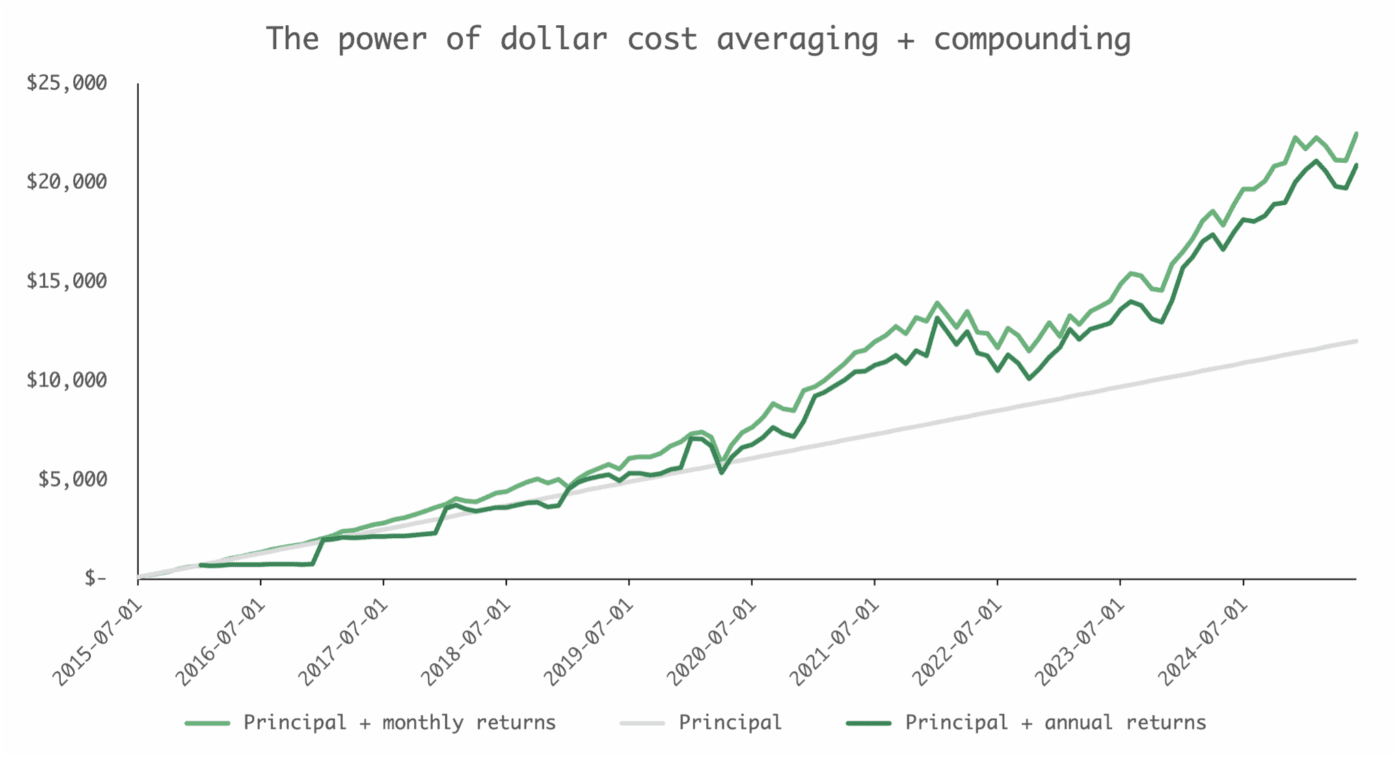

In this example, let’s consider a basic savings strategy as a control group of sorts. Say that 10 years ago, in July 2015, you started to put $100 a month towards saving and investing. That’s the grey line in the first chart below.

Now, let’s say you decide to invest your money. Starting in January 2016, you begin investing the savings you’ve collected ($700) into the S&P. You keep saving every month, but don’t contribute again until January 2017, when you contribute $1,200. And the trend continues. Your investments accumulate gains and losses over the years, and each January you add to the principal. That strategy, represented by the dark green line, helps maximize your savings. 10 years later, in June 2025, you’d have more than $20,800 (some of this money would be in cash, awaiting the next January investment).

Now consider what happens if, instead of investing once a year, you had simply invested $100 every month, instead of waiting until January. This small adjustment—represented by the neon green line—would increase your overall returns by 8%. You’d have some $22,400 at the end of 10 years.

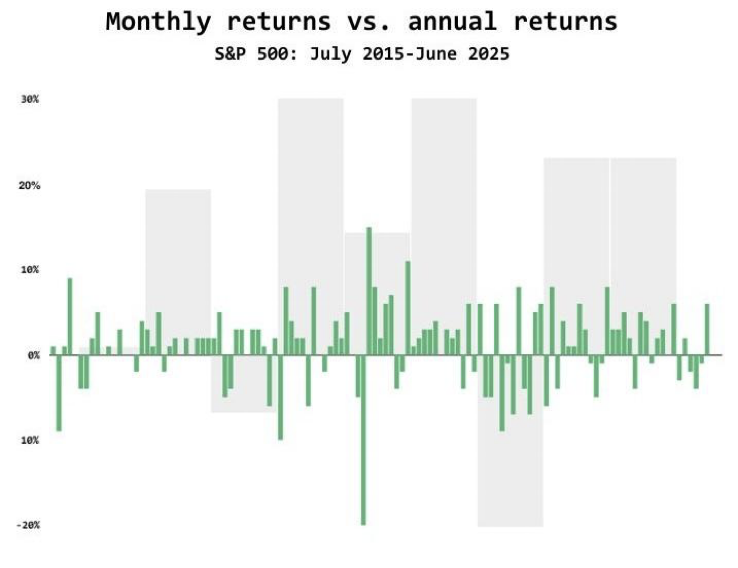

Why the increase in returns? Simply put, buying every month—or dollar cost averaging—increases your chances to buy low. There’s more ups and downs in the market in the short term than in the long term. Consider how monthly returns compared to annual returns during the period in question.

In other words, taking a consistent approach to investing can help you tap into the elusive “buy low, sell high” formula without having to focus on market performance and timing.

If you have questions about dollar cost averaging or want to discuss your investment strategy, contact us to discuss.

*We used S&P 500 index returns (all data provided by S&P Dow Jones, LLC via the St. Louis Federal Reserve) for this example. However, you cannot invest directly in a stock market index such as the S&P 500. Funds that track the S&P 500 charge fees that impact performance, meaning actual returns, even for indexes that track the S&P 500, may vary slightly from these numbers. The examples in this article are meant to be educational in nature. Past market performance does not predict future performance, and individual investment returns may vary.

The secret to selling high

As the old adage goes—the secret to successful investing is to buy low and sell high. Unfortunately, even the most proficient investors rarely know how to buy at the bottom and sell at the top. As a result, attempts to time the market rarely produce the desired results.

However, diligent investors can still apply the principle of buying low and selling high to their portfolio. When it comes to buying low, strategies like dollar cost averaging can help ensure investors buy consistently, including during dips and selloffs, increasing their chances of buying during downturns. (Of course, with dollar-cost averaging, you’re also buying during bull runs.)

When it comes to selling high, you may be able to apply an even more strategic approach. Let’s look at how sequence risk, withdrawal rates, and income planning in retirement can align to create a strategic plan to sell high whenever possible.

What is sequence risk

When you’re living on a fixed income, market downturns can generate an understandable amount of anxiety. When these downturns occur early on in retirement, the effects can be more significant. Remember: If you have $1 million dollars, and lose 20% ($200,000), your portfolio would need to return 25% to make you whole again. ($200,000 is 25% of $800,000.)

To see how significant the order of returns is, consider what happens to a $1 million portfolio in two scenarios.

In the first instance, at left, the retiree withdraws $48,000 a year from a $1 million portfolio invested in the S&P 500.* Over the next 20 years, the index returns an average of 11.3% a year—these returns reflect the actual S&P 500 returns from January 2004 to December 31, 2024.

In this example, stocks returned less than 10% in two of the first four years, then fell 37% in 2008. The retiree’s portfolio falls significantly, to just over $700,000. The retiree might grow concerned that they’d outlive their nest egg.

The crux of the problem? The retiree is forced to sell low. If their portfolio is their only source of income, they’re forced to sell those investments during the downturn.

Now consider our second example at right—the retiree withdraws the same amount from a $1 million portfolio invested in the S&P 500. But in this instance we flipped the order of the returns, starting with 2024 and working backwards to 2004. The average return is still 11.3%, but in this case, the portfolio doubles in value twice. Twenty years on, the balance tops $4.3 million. In this example, the market returned more than 20% in three of the first five years; the investor sold high.

In both of these examples, the retiree is using a consistent selling strategy that didn’t take performance into account.

Income and withdrawal strategies

Deciding when to sell in retirement is more commonly referred to as a withdrawal strategy. While the best approach when saving for retirement is often to simply save and invest consistently, you may be able to take a more strategic approach to selling and withdrawal.

For instance, if the market is underperforming in the early years of your retirement, you may be able to consider additional sources of income to avoid having to sell investments when valuations are low.

A financial advisor can help you strategically evaluate your options. If you have additional sources of income in retirement, such as social security, or a part-time job, you may be able to adjust your withdrawals in down years. Doing so could help extend your savings.

Managing income risk in retirement

Many experts, which now extends to AI and internet advice, suggest a 4% withdrawal rate as a “safe” way to extend the life of your money. However, it’s rarely helpful to think about an income strategy in terms of percentage.

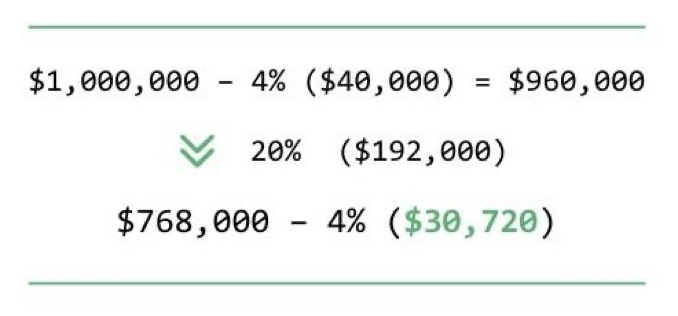

If you have a $1 million portfolio and you withdraw 4%, you have a nice $40,000 income. But what happens the next year if the portfolio loses 20% of its value?

In that scenario, withdrawing 4% the following year would amount to slightly less than $31,000. In other words, your income would fall by nearly 25%, a significant dent. Monthly withdrawals (dollar cost averaging in reverse) can help mitigate some of this risk when selling, the same way it can improve results when buying.

Advisors can help you come up with a more realistic withdrawal strategy that takes your budget, as well as market performance and any additional income sources, into account.

If you have questions about building a withdrawal strategy or income plan for retirement, contact us to discuss.

*We used S&P 500 index returns (all data provided by S&P Dow Jones, LLC via the St. Louis Federal Reserve) for this example. However, you cannot invest directly in a stock market index such as the S&P 500. Funds that track the S&P 500 charge fees that impact performance, meaning actual returns, even for indexes that track the S&P 500, may vary slightly from these numbers. The examples in this article are meant to be educational in nature. Past market performance does not predict future performance, and individual investment returns may vary.